From Civil Unrest to Civic Awakening: The History of the Empowerment Congress

Los Angeles was simmering with tension when Mark Ridley-Thomas won election to the Los Angeles City Council in June, 1991.

Just three months earlier, in March, Rodney King had led police on a long car chase before being beaten by the LAPD officers as a bystander shot video. The footage shocked audiences around the world, but many residents of Ridley-Thomas’ South Los Angeles district saw the brutality depicted as merely the rare public airing of a common occurrence – a pattern of police behavior they had long seen in their communities.

King’s beating was followed two weeks later by another videotaped atrocity, this one in the heart of Ridley-Thomas’ council district. Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old high school student, was shot in the back of the head by Soon Ja Du, a Korean American liquor store owner, after the two had come to blows in the store.

These incidents put Los Angeles in the national spotlight, and would presage the civil unrest of April 29, 1992.

But outside the media spotlight on the tragic violence in South Los Angeles, residents had for years been struggling in quiet obscurity. The 1980s had been a period of public and private disinvestment in the area.

Banks and stores were closing, along with the factories; social services were inefficient and under-resourced. Jobs disappeared in a deep recession, and there were long waits at downsized public agencies.

Teen centers and youth programs had closed; meanwhile, drug dealers pushed cheap, highly addictive drugs like PCP and crack, even as drug treatment and rehab programs moved out of South LA. Financial services had long redlined the area, but when homeowners lost their jobs, the rate of foreclosures skyrocketed and so–called equity scam artists began to prey on these homeowners, particularly seniors.

These and other economic and social conditions drove community activists and advocates in South Los Angeles to speak out and demand accountability from their local government, a movement which drove Ridley-Thomas to the City Council.

The people of the area had long desired civic engagement, spurred by poor land use decisions, police brutality, inferior city services and more. Residents were eager to participate in their local democratic institutions – they just didn’t know quite how. They revered African American representatives like Mayor Tom Bradley, but had for years been overlooked by decision makers and elected officials –at every level of government– who were unwilling to involve them in or even communicate with them about key policy actions.

They had long had the will. They needed a way.

When he took office as a councilman in the summer of 1991, Ridley-Thomas’ constituents had access to a new set of tools to build a permanent vehicle for citizen leadership.

The Empowerment Congress created a structure to channel that activism and coordinate advocacy efforts.

They convened meetings held in the auditorium of the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance building –a landmark African American business—drawing initial groups of 30 to 40 community members.

Much of the attention then was directed at police brutality issues, which dominated the political climate of the time. The Christopher Commission on the LAPD had that year concluded that the LAPD’s management had condoned excessive force by officers, and called for new standards of accountability.

But there was equal passion for more bread-and-butter neighborhood concerns as well, such as enforcement of building codes and zoning standards, street cleaning and enhancement of struggling commercial areas.

The concentrated neglect of such standards not only eroded the often-precarious net worth of working class homeowners by lowering the value of their hard-earned homes, but also degraded neighborhoods by allowing nuisance businesses such as liquor stores, motels and recycling centers to dominate the commercial landscape.

Those early meetings were soon overwhelmed by greater forces. In April 1992, a jury in suburban Ventura County acquitted the LAPD officers who beat Rodney King. Anger at the verdicts set off a wave of destruction throughout Los Angeles, with Ridley-Thomas’ district the epicenter. Businesses burned and civilians took up arms against each other. The Councilman’s district office was also set ablaze.

Those fires of 1992 ignited the civic resolve of Ridley-Thomas’ constituents. Their budding neighborhood improvement efforts begun the prior year were formalized into the Empowerment Congress, with a straightforward motto: Educate, Engage, Empower.

More than 300 residents attended the first Empowerment Congress Summit at Crenshaw High School. Attendance at the annual summits grew rapidly, and the events now consistently draw more than 1,500 participants.

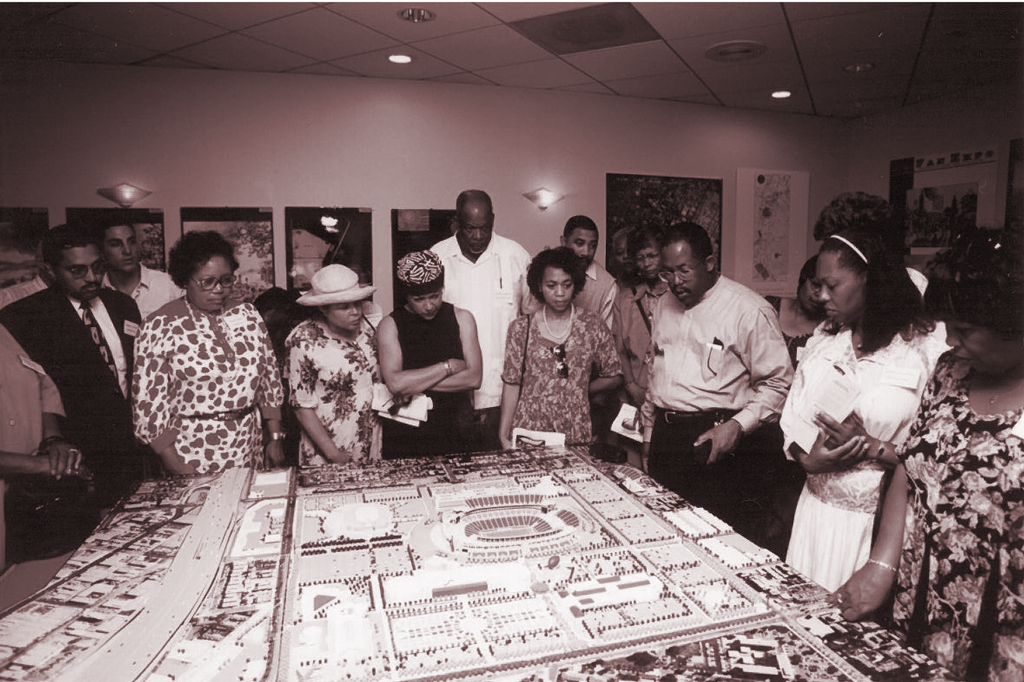

Empowerment Congress members identified issues in their midst through Neighborhood Development Councils (NDC) composed of block clubs, faith-based organizations, businesses, residents and commercial property owners. The solutions they proposed would have an impact beyond their individual homes and blocks.

For example, when an NDC persuaded the city to close off an alley behind members’ houses, they were not only able to plant gardens where others had illegally dumped trash, they also cut off drug dealers and prostitutes from working in those spaces. Collectively, these individual efforts also helped to cut criminal activity citywide.

Similarly, when residents raised concerns about illegal pet breeders operating out of homes and the overwhelming number of stray dogs and cats roaming the streets, the Empowerment Congress led the way to enacting a tough city pet overpopulation ordinance in 2000. As the Los Angeles Times noted then, “while the issue has been debated for decades, proponents have only recently gained the political clout to further their cause.”

The Empowerment Congress emphasized land use and economic development – not simply opposing liquor stores, but promoting business standards to ensure merchants enhanced neighborhoods rather than promote crime. Innovations like the city’s “linked banking” ordinance came from the Empowerment Congress and were legislated by Councilman Ridley-Thomas.

These efforts developed Empowerment Congress members’ sophistication in complex matters such as redevelopment, information and technology, animal regulation and more.

The Empowerment Congress inspired the creation of the City of Los Angeles’ Department of Neighborhood Empowerment, guiding Councilman Ridley-Thomas to introduce the motion to create the department in 1997. By 2004, the city agency had established a network of 90 neighborhood councils.

Many of those neighborhood councils today serve areas known by names resurrected through an Empowerment Congress effort, the “Naming Neighborhoods” project. Concerned that many distinct communities were lumped together as “South Central,” often with pejorative effect, the Empowerment Congress organized efforts by residents to research the history of their neighborhoods and discuss their shared identity and aspirations through block club meetings, area assemblies and workshops at the annual summit.

The result was the restoration of historic, but often forgotten, neighborhood names, including Chesterfield Square, Baldwin Village, Green Meadows and Jefferson Park.

With Ridley-Thomas’ move to the State Legislature in 2002, the Empowerment Congress’ emphasis shifted from the immediate neighborhood concerns that can be addressed by the City Council, to matters such as larger-scale public works projects.

Many Empowerment Congress stakeholders took on state issues even as they remained committed to city advocacy efforts, and new members with particular interests in matters under state jurisdiction came aboard.

Empowerment Congress members led Ridley-Thomas in the state legislature to successfully introduce legislation establishing health clinics based in public schools, to make it easier for families –especially those without cars– to obtain medical treatment.

The Empowerment Congress also convened annual state budget summits, demystifying a budget process bewildering to many but vital to everyone.

After Ridley-Thomas was elected to the Board of Supervisors in 2008, Empowerment Congress members were vital in building grassroots political support for the new Martin Luther King Jr. Medical Center, replacing the hospital that closed in 2007 after reports of deadly malpractice. Empowerment Congress members mobilized in full force to win approval for the Crenshaw/LAX light rail line, a project that had languished for nearly 25 years.

Los Angeles today, after more than 30 years of Empowerment Congress advocacy, has seen remarkable progress in some of the areas that had been crisis points. Crime has consistently fallen in Los Angeles even during the current economic recession. The LAPD is now a majority-minority department, nationally recognized for its engagement with the communities it serves.

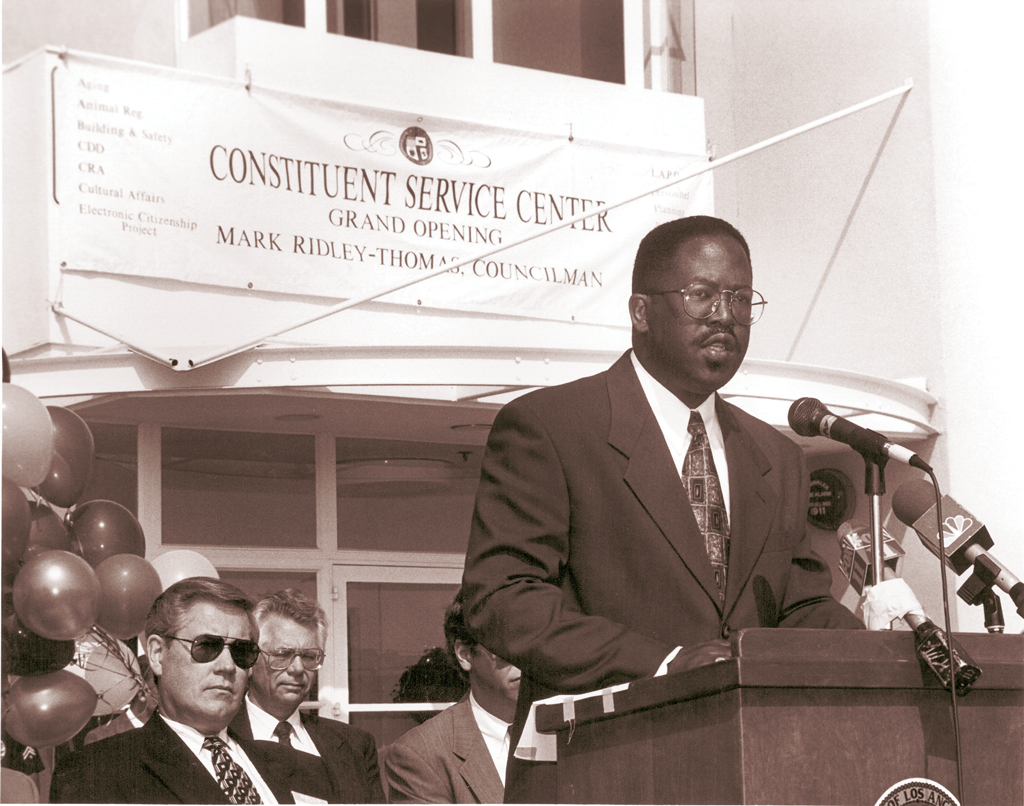

The drop in crime has also occurred in South Los Angeles, where many new businesses also have improved the quality of life for residents. A full-service grocery market has replaced the liquor store where Latasha Harlins was shot. Ridley-Thomas’ former City Council district office, burned in 1992, was rebuilt in 1996 as a Constituent Service Center, a “mini City Hall” with representatives of 15 city departments located at the site as well as meeting space for community gatherings.

Yet the deep, underlying distress prevalent at the time of the 1965 and 1992 riots remain. High school dropout rates, unemployment and health insurance rates are actually worse today than they were in 1965 and 1992. Income inequality continues to widen and the Empowerment Congress tilts against a broader trend of disengagement from government.

Today, the Empowerment Congress is able to use tools, such as its website, standing committees, and annual summit, to engage large numbers of Los Angeles County residents, covering a far greater area than the original City Council district it served. It has also partnered with the Kellogg Foundation to train government and community leaders from across the nation in the Empowerment Congress’s civic engagement methods.

After many years, the particular challenges may differ, but the underlying cause remains the same: persistent racial and economic disparities in every aspect of the community environment – education, wages, housing, health. More than ever, the Empowerment Congress is needed to equip residents to put forth an agenda representing their interests.

A perfect example of the need for the Empowerment Congress’s vigilant activism is the development of the Crenshaw/LAX light rail line. Empowerment Congress members were the foundation of a successful effort by then-Supervisor Ridley-Thomas to win MTA approval for a Crenshaw rail line, a long-deferred dream of former Mayor Tom Bradley and U.S. Representatives Julian Dixon and Diane Watson.

The rail line is now reality and, through advocacy in partnership with Empowerment Congress, a station at Leimert Park is part of that community resource. While construction remains underway on the line, the inclusion of a Leimert Park station is just one of the many outcomes that are a result of strong civic engagement and reciprocal accountability.

The Empowerment Congress’s reach may continue to evolve, but its founding purpose remains: Educate, Engage and Empower.